Wine is for drinking, but also for storing, for owning, even for speculating. Because not only wine can change, its prices do too - they rise and fall and rise and fall... Especially for those wines that can, indeed must, be stored, above all because - in the best case - they develop over the years, mature, become better and better. Even when they have passed their peak, they often remain monuments of wine culture, not infrequently also prestige objects, which for many are an honour and therefore desirable to own. A well-designed, well-maintained wine cellar can be a safe, a treasure trove in which capital is stored in the form of bottles.

|

| Stored treasures (Photo: P. Züllig) |

The value of expensive bottles is not much different from the value of shares. Sometimes the market value rises, sometimes it falls deep into the cellar. And like securities on the stock exchange, wines are also traded, bought to be sold again later - whenever possible - at a profit. It is a game of supply and demand, with the decisive difference to shares that with wine there is a natural expiry value, namely when a wine is "over" (René Gabriel's term), has not been stored properly or the producing winery has lost fame and glory. No wonder that the wine industry - which plays in the top league - defends the good reputation and the sounding names, the quality and prices, the reliability and exclusivity, the success and renown of the famous wineries and producers. Bordeaux has shown how the merry-go-round is kept going, vintage after vintage, year after year. People have long since become accustomed to it, believing that it will go on and on. Slumps are not admitted, not communicated; they could be harmful for the business. Instead, new strategies are constantly being developed to stay in business - even with poor-quality vintages. The show must go on!

|

| Wine archive at Château Latour in the Bordelais (Photo: P. Züllig) |

Nevertheless, there are clear signs that the business is faltering, that the market value of the share of wine is sinking and sinking - although the (fictitious) prices are still rising and rising. Even the - in our eyes - wine novice Chinese are no longer buying at any price. A year ago, a seller - even for the mediocre quality second wine of Château Lafite-Rothschild - easily fetched ten times the former purchase price (which was around 30 francs). A bottle of the Premiers Crus could hardly be bought for less than 1,000 francs even at the subscription stage, and the prestigious Pétrus estate could afford to let the subscription price for a bottle rise to more than 3,000 francs. In this game of rank and name, money and fame, the merchants were ahead for a long time. They bet on risk and won, especially in the past ten years or so when prices exploded. Now the tide seems to have turned, even if no one really wants to admit or acknowledge this. After all, the admission of a bad speculation could (with some certainty) send the share price of wine plummeting.

I see before me the stunned expression of a wine merchant, at one of the last auctions, where the "best values" could not find a buyer even at the "discount price". Now I recently stood in one of the large wine shops where the perplexed merchant works as a branch manager and saw - no less stunned - the top prices at which the same "best values" are offered here. I can well understand then that every wine merchant no longer understands the world! "Not bought at that price," is still ringing in my ears weeks after the auction. "Unbelievable!"

|

| Wine exchange in Zurich. Who bids more? (Photo: P. Züllig) |

But they don't want to admit the crisis, and they certainly don't want to talk it up. The fact that the warehouses of many wine wholesalers are full to bursting - especially with vintages that can hardly be sold (at the given high cost prices) - is kept quiet. Just "one bad rumour" could have a devastating effect on market development. So one's own suffering (from falling prices) is described, for example in an auction catalogue: "At the moment the wind has changed a bit; if you are not looking for 2009s, there are more and more interesting prices, the seller's market has become a buyer's market. Among other things, this time there are also many mature wines (in best condition) on offer, which have to find a buyer at almost any price. That means the first call of some catalogue numbers sometimes starts at less than 50 per cent of the lower estimate!" Sellers - in auction jargon we speak of consignors - as do-gooders, benefactors or even "Samichläuse"? Hardly. These are simply veiled signs of a market in crisis.

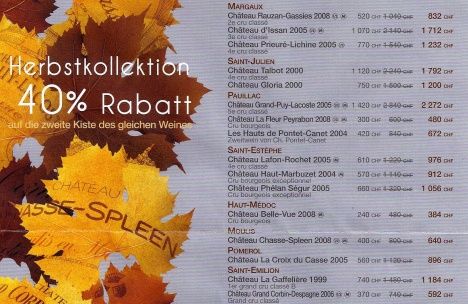

Even more drastically, Millesima - one of the biggest players in the subscription business - is trying to boost the market with its promotions. "40 % discount", of course, not just like that, as a gift, but only "on the second case of the same wine". Anyone who thinks that the less saleable wines are being sold off here is mistaken. Of course, none of the really great wines, the prestige wines, are included. But we do find a Château Grand-Puy-Lacoste (from the "top vintage" 2005) on offer - a single bottle would otherwise cost well over 100 francs. The "eternal insider's tip" from Moulis, Château Chasse-Spleen, also makes an appearance; it is now around ten francs cheaper than it was in the same house's subscription back then, namely it costs around 26 instead of 36 francs.

Admittedly: Two examples are no proof of a crisis situation, especially if no one is allowed to admit it. There have always been similar promotions, especially in autumn, before the holidays around Christmas time. The fact that wine advertising is obviously being intensified may also be a coincidence or an expression of booming business. But anyone who has to empty the letterboxes stuffed with wine advertisements every day - both on the doorstep and on the computer - inevitably becomes perceptive and starts comparing prices and offers.

|

| Bait offer: 40 per cent discount (Photo: P. Züllig) |

Anyone who assumes that retail prices will now fall drastically is sorely mistaken. In the top segment, they are sliding down a bit, but essentially they are staying at the level they climbed to - not only in the Bordelais, but everywhere where there are prestige wines. No one is interested in a drop in prices, neither the merchants, nor the winegrowers, not even the buyers, because about 70 percent of the wines in this category are returned to the market, often shortly after delivery (about two years after the harvest), but often only after years. A look at the daily eBay offerings shows how the "small trade" in wines is flourishing. More than 15,000 offers appear under the keyword "wine", almost exclusively in "buy it now" (at fixed prices). Even though not all of the 15,000 lots directly concern wines, but may well also contain wine books, bottle openers, labels, souvenirs, etc., there is still a considerable market here with corresponding sales. Many wine lovers also stock up here in the quiet hope of getting their favourite wines at a lower price. However - and this is astonishing - among these 15,000 offers there are only about 50 to 100 real auctions where wines can actually be bought at auction. At the moment - when I browse through them quickly - I don't see a single concrete bid. But they don't talk about that either. It could be that the crisis is coming. Then all the many "small traders" will be sitting on their hoarded treasures or will be forced to sell at a loss.

|

| Private wine cellar - the wines in original wooden crates (Photo: P. Züllig) |

In addition, there are factors that are not directly dependent on the wine trade, but rather on economic and social developments. The wine critic of the renowned NZZ (Neue Zürcher Zeitung) puts it this way: "Subscription sales for the new Bordeaux vintage have been rather sluggish..." Rather sluggish? Catastrophic, an industry insider told me, and the many subscription offers still running (otherwise the en primeur purchase is completed by autumn at the latest) indicate that a system that has worked well for decades is indeed collapsing. Hardly any wine - with the exception of a few speculative wines - can be bought at a lower price in the "pre-sale" (subscription or purchase "en primeur") than about two years later when it comes onto the market. In many cases, the wines are even cheaper on the first market than in the risky forward transaction called subscription.

And another important factor influences the unacknowledged crisis. In all classic wine countries, so to speak, considerably more wine is produced than consumed. This leads - according to the laws of the market - to cheaper prices. Not so with wine. There is an ever-increasing supply of cheap wines - an Amarone, for example, for barely 14 francs, advertised as a top wine at discounters. Anyone who has the slightest idea of winemaking knows that no Amarone can be produced at this shop price, let alone a good one. It's the same with many of the so-called "cheap" wines. Wines that are well made (of which there are more and more!) and that have to bring in the production costs and a profit, are being pushed under the radar. These are the wines around 20 to 30 francs. They are having a harder and harder time on the market.

But there are also the famous names, ennobled year after year with points and flowery words, which defend their price as long as they can. And it goes on for a long time, until the glorious names are worn out and scrapped. Until you - as a wine lover - don't have to drink them at least once a month, once a year, once in your life, to be a real, crisis-proof wine freak.

Sincerely

Yours/Yours