Since early childhood, an image has stuck in my mind: a bundle of wood tied together, with an axe in the middle - the coat of arms of the canton where I grew up. Symbolic, as coats of arms often are: At school we continued with similar symbols and messages: the three men who swore on the Rütli to stand by each other in times of need and danger and thus founded the Swiss Confederation: "We want to be a united nation of brothers!" But soon the picture changed, and not only in history lessons.

Since early childhood, an image has stuck in my mind: a bundle of wood tied together, with an axe in the middle - the coat of arms of the canton where I grew up. Symbolic, as coats of arms often are: At school we continued with similar symbols and messages: the three men who swore on the Rütli to stand by each other in times of need and danger and thus founded the Swiss Confederation: "We want to be a united nation of brothers!" But soon the picture changed, and not only in history lessons.The hero emerged, the loner who masters life, whose deeds are admired. He sets standards and replaces the community. The idea of uniting in so many areas of life - actually the cooperative idea - is increasingly discredited. This can be seen particularly clearly in agriculture, including viticulture. There, cooperatives - at least in the last few decades - have lost their reputation for collective size and strength. The hero is now the winegrower, the winery that makes the best wine.

But do individual winegrowers - traditionally they are family businesses - really make the best wines? Is the gap to the cooperatives really as big as is repeatedly claimed? Isn't it also increasingly large companies - global players - that dominate the wine business? Most of the large châteaux in Bordeaux have long belonged to companies that have little or nothing to do with wine. They are investment objects for insurance companies, companies in the luxury sector, the real estate trade and, increasingly, foreign investors. The fairy tale of the capable winemaker, of a family business linked to wine for decades, even centuries, has long been outdated. The most important representatives of the wine dynasties in the Bordelais manage ten and many more wineries and employ the most famous oenologists, flying wine makers, in the operational area of their companies. Wine cooperatives hardly have a place there, let alone a chance.

In other large wine regions of France, cooperatives are much more important. Languedoc-Roussillon, for example, has been a wine region dominated by cooperatives for more than a hundred years. Despite many mergers, there are still more than 250, where many thousands of winegrowers deliver their harvest year after year and where the wines are then pressed, vinified and later marketed.

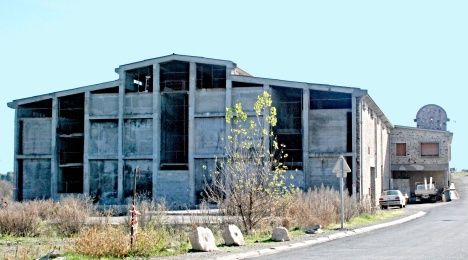

|

| Historical cooperative building in Agde% Hérault (Photo: P. Züllig) |

The relatively small cooperative Caves Richemer (Agde/Marseillan) alone - only one of more than 200 active cooperatives - unites 450 winegrowers and extends over three municipalities, which, however, are outside the AOC areas. So this is where "Vin de Pays" is made, which today is called "Indication géographique protégée" (IGP). When I first stood in front of the stately cave a good thirty years ago, although it was already almost dilapidated, it was three large concrete tanks that caught my attention (they have since given way to a car park). This is how I imagined winegrowing in Languedoc-Roussillon: ponderous, dusty, outdated, stuck in mass production. After all, 80 percent of France's "vins de pays" come from this region. When I then - a few years later - watched in the cave of Saint Saturnin how the probably machine-harvested grapes were delivered, my mind was made up: cooperatives produce wines of inferior quality. I hardly bought any of their wines any more.

|

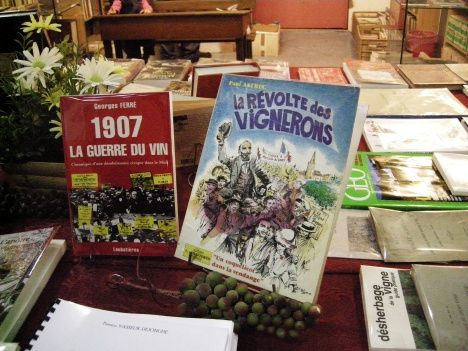

| The 1907 winegrowers' revolt in Languedoc - birthplace of the wine cooperatives (Photo: P. Züllig) |

Only gradually did I realise the importance and historical background of the cooperatives in Languedoc-Roussillon. When the winegrowers in the south of France were miserable at the beginning of the 20th century and prices collapsed due to overproduction, imports from Spain, Italy and Algeria as well as the adulteration of sugar wines by merchants, the legendary winegrowers' revolt (1907) took place, which was finally put down by the military. As a result, the winegrowers resorted to self-help, and the Coopératives, or cooperatives, came into being. Today, one of their majestic buildings, built in the 1930s and 40s, still stands at almost every village entrance, documenting the self-confidence and pride of the winegrowers. Together they had become strong.

|

| Imposing cooperative in Ventenac% Minervois% on the Canal du Midi (Photo: P. Züllig) |

But then came the 1970s and 80s. The situation in viticulture changed thoroughly; wines from the "new wine countries" came onto the market; cheap wines, such as those produced in the Languedoc for decades in 80 percent of cases, were less and less in demand; new cultivation and growing methods ensured better quality; marketing became a decisive factor for success. In addition, the often cumbersome cooperatives were unable (or unwilling) to keep up with the rapid development, and many of their caves were hopelessly outdated. More and more good winemakers left the community and set up their own businesses. Others tried their luck in selling their vineyards to foreign winemakers and investors, not least to the top dogs from the Bordelais.

|

| Former cooperative building (built in 1946) of Causses-et-Vayran% Hérault; in the foreground were once the large concrete silos (Photo: P. Züllig) |

Protesting winegrowers, who are really getting worse and worse again, almost like a hundred years ago, do not shy away from acts of sabotage and violence. An image that made the headlines in the world press. But this is only one, the loud side of the current situation. There is little talk about the other side, it is hardly taken note of. Many cooperatives have long since set out and faced the new situation - also with state help - and have entered the globalised market. Some of them with considerable success. Today, good, even very good wines come from cooperatives such as Roquebrun, Tuchan, Berlou, Cabrières, Castelmaure, Leucate, Rocbère, to name just a few examples. Many cooperatives have long since stopped focusing on mass production and cheap wines; they offer good, sophisticated wines, usually at a reasonable price. The cooperative idea is also beginning to assert itself in terms of quality. They are not afraid to seek advice from good, even the best oenologists. In addition to the "simple wine", there is almost always a line "en haut de gamme" (top wines). Some cooperatives have even created domaine or châteaux wines by vinifying certain plots separately and giving them their own name: Château Albières is one such example - from Cave Berlou.

But cooperatives still have a hard time: they are shunned in wine lovers' circles. Wine guides - be it Hachette or Bettane & Desseauve - do not include five percent of the cooperatives in their lists. In my experience, this has less to do with quality than with market interests. Buyers of wine guides are hardly interested in coopératives, but rather in lone warriors, winemaking heroes, big and also smaller names. Cooperatives, where individual winemakers remain nameless, where only the "overall performance" counts, are of little interest to wine lovers.

The former "core business" of the cooperatives, wines for everyday consumption, is also faltering. Due to the significant increase in quality (including yield reduction), even simpler wines have become significantly more expensive. Still cheap - even compared to other beverages - and often even with a sensational price-performance ratio. But people here are - traditionally - still used to being able to buy wine for a few cents or a few euros, across the street, so to speak, "en vrac", straight from the barrel. In this area, the competition (especially from abroad) has become almost unbeatable, and hardly anyone talks about quality. The cooperatives, which are also concerned about their "good reputation", cannot (and do not want to) keep up.

|

| New appearance of the cooperatives: fresh% modern and contemporary - Cave Richemer (Photo: P. Züllig) |

The cooperatives - today for the most part well-managed and well-equipped, quite capable of making the best wines - are always caught "between a rock and a hard place", so to speak: shunned by some (or not quite taken in their stride), pressured by others to produce even cheaper and more trivial wines. It is not easy to position oneself correctly. The preferred solutions of the hard-pressed winegrowers so far are: Independence, whenever and wherever possible, or making completely different wines - different grape varieties and mainstream, as the market demands, or uprooting the vines and collecting the EU premium. None of this can solve the Languedoc problem. Some of the winegrowers who have become independent manage to survive in the tough cut-throat competition (in France's largest wine region) and to market their wines profitably. But they are - measured by their number - only a few. Others give up or radicalise themselves - in smaller and larger groups. Maybe the cooperative idea has a chance again: "United we are strong" The memorable image of my youth gives me hope and probably gives hope to the many cooperatives as well.

Sincerely

Yours sincerely