Yes, there is such a thing as a "wine language", that is undisputed. But is there also a uniform language, a "doctrine" about it? That's where my serious doubts begin. After reviewing hundreds of wine reviews - from perhaps the ten best-known (and most respected) wine critics - I have to conclude: There is only part of it, maybe half. "A technical language in the field of wine has existed for over 150 years. Maybe you should also read Peynaud, that would be beneficial", a good friend and wine expert, whom I appreciate very much, precisely because he taught me a lot about wine, lectures me. "The High School for Wine Connoisseurs" by Emile Peynaud has been on my bookshelf for a long time, whether the content has reached my head, others have to judge. I think it has!

|

| The high school for wine connoisseurs by Emile Peynaud (Source: P. Züllig) |

"Tasting wines is not as easy as one generally assumes, but talking about them is often even harder. Nevertheless, sensory perception and language are inextricably linked in the evaluation of and communication about wine," states a well-documented article on biowein-journal.at.

In his blog on vinolog.de, editorial colleague Carsten M. Stammen in an excellent essay: "When wine language becomes too dissolute, when too many images and metaphors come together and overly (attempted) original analogies are constructed, when sentence structure takes on rather adventurous forms, when flowery language becomes florid and more style flowersflowery language becomes flowery and produces more stylistic flowers and catachreses than sensible, factually appropriate and comprehensible descriptions - then wine criticism has failed in its purpose and at best serves the author as a refreshment for his own (supposed) genius.“

|

| L'Université du Vin in Suze la Rousse% Rhône (Source: P. Züllig) |

When Wein-Plus recently organized and recorded a conversation with gastronomy consultant Otto Geisel, wine trader Martin Kössler and wine critic Marcus Hofschuster on the topic of wine language, it remained quiet for the time being - at least publicly - in the forum at Wein-Plus.eu. On Facebook, however, the topic was immediately taken up. "A valuable discussion. And yet, I have the impression that the participants more or less talked past each other. In the end, it is and remains unclear how it is supposed to look concretely, the 'new language' of wine. And which role numerical schemes play", Werner Elflein writes at "Weinfreaks". Promptly, another 118 comments follow, Facebook-like, sometimes short, sometimes serious, sometimes less. Yet, the topic seems to be burning under the nails even in sworn wine lovers' circles.

I then picked up the thread in the rather flagging forum of Wein-Plus. And lo and behold, something stirred. First of all, I was thoroughly instructed: "Applied technical language is simple in itself, can be translated into all languages effortlessly and unambiguously (or uses fixed terms that are understood in absolutely the same way) and serves to convey unambiguous information that is understood in the same way everywhere to someone else who doesn't know something. Period," Koal writes. Right he is. "Period."

Except is it really "absolutely equally understood terms" that manifest themselves in wine language? No point there for me, but a big question mark. Even if many traditional terms have been (more or less) defined in the meantime, in the vast majority of cases, sensory terms are not measurable quantities, but perceptions and - when communicated in language - paraphrases, analogies, in short, terms that can be interpreted through one's own experiences (perception).

|

| And now% what is to be said about wine? (Source: P. Züllig) |

"Although some scientific institutions have been striving for greater uniformity and precision of a wine language for several decades, various aspects seem to stand in the way of an exact diction...", says the author in the Biowein-Journal, referring to more than 60 (documented) citations in the detailed justifications.

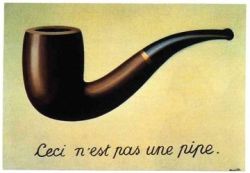

But let's assume that there are "exact terms of analytical nature, like aromas/tones of green grass, roses, nutmeg, tobacco and vanilla, as well as astringent, acidic and long finish, which are also objectively comprehensible because they are known and verifiable by everyone. They are recognized among experts as synonymous terminology and are universally valid." "A peach is a peach is a peach," I am lectured on the forum. A smoking gun?

Anyone who deals with perception and has eaten peaches also knows from personal experience that this is not true, or just part of the truth or accuracy. "A peach is not a peach, is not a peach," is not so much assertion as experience. But "that's not the issue at all," I'm told, "it's about standardized language, nothing else." True (even from my point of view), it is about language - in this case, wine language. And language is not so unambiguous, otherwise we would not, for example, constantly and repeatedly - as now in the discussion about wine language - talk past each other.

|

| René Magritte% "Ceci n'est pas une pipe." (Source: P. Züllig) |

Wine language is no exception. Even if there is always a struggle for unambiguity in communication, this is not only laudable, but a prerequisite so that wine evaluation is not only an instrument for experts, but also serves (or can serve) the wine and the information of the consumer. This is exactly where the core of the problem lies.

The wine language is largely incomprehensible for the so-called layman because it is simply not comprehensible in many expressions and combinations. Wine language - like so many technical languages - has largely detached itself from the object (the wine) and the people concerned (the wine drinkers). "And a fortiori, a technical language is not there to convey anything to the unsophisticated consumer", is written in the forum. So experts among themselves! Producers, critics, trained people gathered around a product. The consumer of this product has to stay outside. There you go!

|

| Ready for tasting (Source: P. Züllig) |

It is this arrogance, after all, that makes the language of wine incomprehensible and even suspicious to many. On the one hand, this absoluteness in an area, namely sensory, which cannot be set so absolute. Not only in terms of content, but also in terms of language, because in large parts it is not about abstract numbers, about physically measurable values, about defined formulas, but about perception, which is closely connected to the perceiver, the subject. On the other hand, there is the consumer, who wants, indeed needs, reliable statements in order to judge a product that he selects, buys and pays for. Especially as the range of products is infinitely varied and large and also varies from year to year, from harvest to harvest, from development to development. A product that is also advertised with all the bells and whistles imaginable.

Is it any wonder that the "uninitiated layman" wants a language which he also understands, and which is not composed of terms and figures of speech derived from Latin or Greek, or are word creations which may be understood but are hardly used in everyday life?

|

| Talking about wine - communication during tasting (Source: P. Züllig) |

Perhaps wine critics (with all their seriousness and scientificity) should also take note of how people communicate with each other. They don't list facts and terms, they tell each other "stories" again and again. In these stories, there are indeed facts, numbers and defined terms. But the framework is an action, a story, which is almost always understood and behind which there is a statement (message) that can be understood. Language is always an image - a proxy, so to speak - for what is to be communicated. It is standardized to a certain extent in the individual terms, but not in what it wants to express and is able to express in the linguistic sequence and formulation.

The "story behind the story", that is, the message "packed" into each story, we are much better able to read, to grasp, to comprehend than the stringing together of supposedly precise terms. "I bite into a peach, the juice contracts at the corner of my mouth, the pit prevents bigger bites, the fibers get between my teeth, what is still sweet, fruity, soft on the outside hardens on the inside, seems unripe, green and slightly sour. I put the remaining fruit into the bowl. I have to hurry to the grocer's again, the visitor will be here in a quarter of an hour." An everyday story. Why do I tell it? "A peach is just not a peach, not a peach!"

Sincerely

Yours